Stuff legends are made of

Share

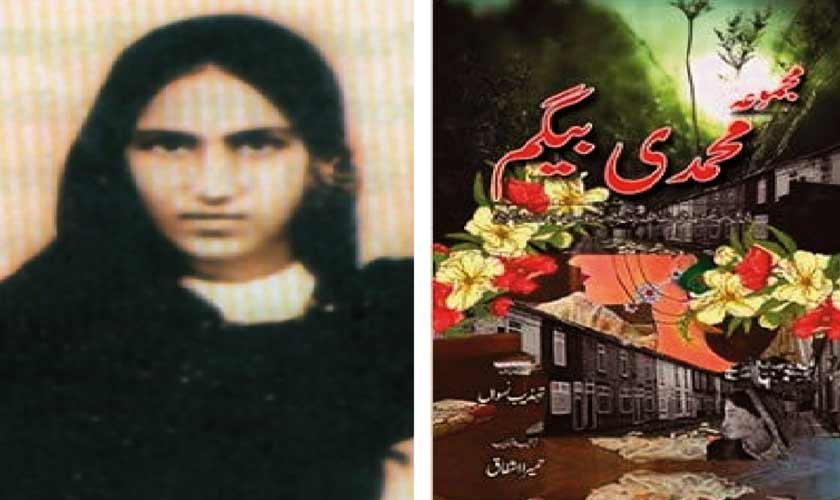

A compilation of the works of one of the pioneers of Urdu print culture – Muhammadi Begum

Even today, the role of women is not an apriori in our society. The subject raises hackles and is rudely reacted to by a big section of the population.

Since colonisation, women’s education and public role had become more cantankerous, a sticking issue in the Indo Muslim culture. But few, very few, saw its importance and still fewer went public about it.

One such person was Muhammadi Begum who began focusing on women – not as the objects of male desire or breeding machines but – as living human beings with a definite role to play in modern societies. It could be seen as a very radical step because the general tenor had been on keeping women at home and not exposing them to public life. Even Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, the pioneer of modern education among the Muslims, was not that keen on women’s education. He preferred men to be educated, to ‘play a greater role in the affairs of society and government’. It was generally seen that Muslims had been marginalised by other religious denominations because of their lack of modern education.

But he was wary of women’s education if not outright hostile to it. He had faced so much bile while advocating modern education for men that he was not willing to take any more challenges in his life. It was left to a junior contemporary, Sheikh Abdullah, to carry the torch of education forward. In the process, he was able to set the ball of women’s education rolling at Aligarh by the beginning of the twentieth century.

But many women in history felt the urgent need for their kind to be educated and one of them was Muhammadi Begum. All her life, through her personal example and her written works, she forcefully advanced the cause of women in a world that was fast-changing and required a corresponding change in people’s minds.

She began writing mainly because she wanted to bring about a change in the way people thought about women and their education. It was necessary because for any change to happen, it is essential for people to be conscious of the value of that change. It was also important because she lived in an extremely conservative society, where exposure of women was considered a question of shame. At the age of eighteen, Muhammadi Begum took up the editorship of Tehzeeb-e-Niswan, an Urdu periodical for women. She continued editing it all her life.

Delhi, Punjab, United Provinces and Hyderabad Deccan formed the bedrock of Muslim culture in the subcontinent. It was the Muslims of these regions who were the hardest to change. People were too set in their ways and any change was seen as being thrust upon them. There must have been a great deal of resistance because the ruling elite always see any change as a threat to a sanctified set of values and thus a move against the status quo. The Muslims of India had been deposed from power and for survival sought refuge in a moribund culture and social patterns.

They were, hence, averse to change. In the less privileged sections of the society, a change was welcomed as an opportunity. The reaction to change was huge among the Muslims.

Muhammadi Begum, supported by her husband Maulvi Mumtaz Ali, launched the Tehzeeb-e-Niswan and propagated a more open view about people. They addressed the problems of the general public mainly from the point of view of women, not only as appendages to men.

The backlash to this initiative was severe and both the husband and wife were lampooned to the extent of threats and abuse.

In this collection, Humera Ashfaq has included Begum’s three novels, Aaj Kal, Safia Begum and Shareef Beti; an adaptation Chandan Haar; and her prose works Aadab e Mulaqaat, Rafeeqe Aroos, Khaanadari and Sughar Beti. There is also a biography of Bibi Ashrafun Nisa Begum.

Deputy Nazeer Ahmad also wrote about women but his works mainly consisted of tutorials on how to be good wives, daughters and mothers, apart from being obedient members of the family. Even in his novels, any change in a woman’s standardised behaviour was seen as being pliant about the western culture and hence seen as a negative characteristic. Muhammadi Begum placed her characters in situations where debating the value of change without being judgmental was preferred.

She was not a pamphleteer and did not air slogans. Since she wrote fiction, the novels gave her ample opportunity to treat the entire question of the needs of a changing order in a comprehensive manner. More aspects were taken into account as well as the human angle which is the most important because the ideas have to be transformed into values to become part of the daily existence of a society. The ideas exist but the transformation of making values out of them can be done in fiction, particularly the novel.

Her prose was very lucid and she wrote with an idiomatic flair, generally known as the begmati zabaan. She was obviously a pioneer and laid the groundwork for more women writers who followed her to deal with the complexities in a more adroit manner.

She also wrote non-fiction and the moral tone is more obvious in those writings. But it is not exclusively morality that she pandered to. By necessity, she placed it in a larger framework.

Born in Delhi, she lived all her life in Lahore and through the power of the pen, along with her husband, focused on change and its positive fallout rather than mourn a lifestyle that was gone and could not be relived. She hardly peddled nostalgia.

Majmua Muhammadi Begum

Compiled by: Humaira Ashfaq

Publisher: Sang-e-Meel Publications

Pages: 616

Price: Rs. 2,200/-

Original Link:

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/655864-stuff-legends-are-made-of